The de Blasio Revolution (Part II)

Bill de Blasio takes the Democratic primary for Mayor by storm, or how the Democratic establishment sowed the seeds of their own defeat.

Dante de Blasio, sitting in what appears to be his family living room, faces the camera and the first thing he says is “I want to tell you about Bill de Blasio. He’s the only Democrat with the guts to really break from the Bloomberg years.”

The advertisement advances this message of change in two primary ways. Firstly, on a substantive level, with Dante noting how de Blasio will shift the cost of economic recovery from overburdened and neglected public services onto the city’s wealthiest. Secondly, on a deeply personal level by showcasing Bill and Dante, father and son, walking through brownstone Brooklyn, in addition to laughing around the kitchen table with Bill’s wife and Dante’s mother Chirlane McCray. Once again, de Blasio draws the biggest possible contrast with Michael Bloomberg. Whereas Bloomberg was a remote tycoon who was most at home in the board room, de Blasio was a Brooklyn family man with a Black wife, son, and daughter and a family that looked like New York.

Perhaps the sort of Obama-era post-racial optimism of the ad would not hold water in a post-Ferguson, post-Eric Garner world, but at the time it was an absolute hit. The ad garnered over 500,000 views on YouTube, on a channel where the average view count on campaign videos was below 1,000, and was repeatedly broadcasted on television screens across the city. Later, TIME Magazine would even claim it won de Blasio the primary.

It’s worth considering this confluence of the change message and the city’s substantial African-American vote. We discussed in Part I about how Black voters were the voters who remained the most loyal to the Democratic ticket against Bloomberg in 2009. Of course, Black voters were the most loyal Democratic voters in New York City period. This loyalty was generously repaid in 2009 by much of the Democratic Party establishment either tacitly or openly supporting Bloomberg for a third term against the city’s first Black Comptroller Bill Thompson. For her part, Christine Quinn, in addition to passing the legislation that allowed Bloomberg to run in the first place, endorsed Thompson so late in the race that in total indignation he refused to appear with her while she endorsed him.

The “Black vote” in New York City is far from a monolith, and there are often significant differences in how Black New Yorkers depending on where they live, for example, in Harlem (whose Black residents usually trace their roots to the Great Migration) or in Jamaica (which often includes more recent immigrant Caribbean-Americans). If not where they live, then how old they are, or whether or not they own their home. Generally speaking however, the majority of the Black vote rarely goes to white progressive or liberal reform candidates in competitive New York City primaries. The reasons for this are worth a more comprehensive analysis then I am qualified to offer, but what matters for this discussion is that de Blasio, a white progressive from Park Slope on paper would not have been a serious contender for the Black vote. By comparison, Christine Quinn had the endorsement of prominent labor unions with heavily Black memberships, and Bill Thompson himself was running for a second time.

But by positioning himself as the strongest break from Bloomberg, de Blasio tapped into a current in Black New York that his opponents either didn’t see or were unwilling to unabashedly approach. On nearly every issue, de Blasio sought to draw the biggest distance between himself and the incumbent. On inequality, de Blasio spoke of a “tale of two cities” and promised to end Bloomberg’s cuts to public services and tax the rich. Black New York was slammed by the financial crisis, especially Black middle-class homeowners in eastern Queens (consider historic Black neighborhoods like Addisleigh Park) who were disproportionately foreclosed upon. Bloomberg’s policies made them finance the recovery, while de Blasio offered an alternative. On Stop and Frisk, de Blasio was the only candidate to support legislation to allow New Yorkers to sue the city for racial profiling.

While it is certainly worth considering the dynamics of the Black vote specifically, the effectiveness of the contrast between de Blasio and Bloomberg went well beyond just one demographic. As the campaign ramped up it became clear that de Blasio was a real contender. At the June 19th New York One debate, de Blasio received wild applause for his attacks on the Quinn-Bloomberg budgets which slashed early childhood education funding. De Blasio offered a fundamentally different approach then the political status quo of New York City. A status quo so terrified of capital flight that any and all spending cuts, no matter how austere, would be preferable to skimming a small amount of wealth from the top. De Blasio’s alternative message of economic justice was resonating.

There was however, a different name who was also offering the politics of change. His name was Anthony Weiner. Yes, that Anthony Weiner. In his 12 years in Congress, Weiner had been an iconic progressive fighter, a man who had been a passionate supporter of nationwide single-payer healthcare and real critic of President Obama from the left. That was all before he resigned in disgrace after sending sexually explicit photographs to a woman on Twitter. Nevertheless, the married man insisted he was a changed person and would make a splendid Mayor. For a while, voters seemed to buy into this idea and Weiner became the frontrunner, before he was once again exposed for sending sexually explicit photographs over the internet and his numbers crashed. Weiner’s collapse largely was to de Blasio’s benefit, who stood alone as the only change candidate with any credibility.

As the summer rolled on, Quinn sank beneath the waves despite her machine support and the endorsement of The New York Times, unable to escape her decision to give Bloomberg a third term. The establishment it seems, had critically miscalculated. The race seemed to turn into a two-horse race between de Blasio and Bill Thompson. Thompson offered contrast with Bloomberg, he did run against the Mayor in 2009 and was a sharp critic, but his moderate approach did not lend itself to the same populist fervor as de Blasio. De Blasio was widely considered by the frontrunner by late summer, and was attracting serious hype and crowds at a level that would be considered surprising to younger New Yorkers who only remember the tail end of his Mayoralty.

Whether it was his focus on inequality, his principled opposition to stop-and-frisk, or his family story, he was making serious waves. De Blasio received another boost when a federal judge ruled stop-and-frisk unconstitutional and a violation of basic civil rights, vindicating his long-held position and humiliating Bloomberg. De Blasio’s competitors were so wedded to the political paradigm that Bloomberg had built, so scared of being perceived as soft-on-crime, that they had avoided de Blasio’s hardline opposition, but now a neutral arbiter was agreeing with Bill.

New York law prior to the advent of ranked choice voting for municipal primaries stipulated that a candidate needed to obtain over 40 percent of the vote to win a primary outright, and winning short of 40 percent meant that a top two-runoff would be held with the second place contender. Polling showed de Blasio hovering around 40 percent, but clearly needed one last push to make it there. Another establishment miscalculation was all it took.

In an exit interview with New York Magazine, the outgoing Mayor was asked about the de Blasio campaign and he blasted it as “class warfare and racist.” The Mayor clarified that he did not mean to say de Blasio himself was racist, but accused de Blasio of weaponizing his mixed-race family for political purposes in a way that was unbecoming of a potential Mayor. If Bloomberg thought his words would scare fence-sitters away from de Blasio he was absolutely wrong. De Blasio pounced, demanding an apology and McCray defended her autonomy as a free-willed political agent. Ouch.

On primary day, de Blasio swept to a first place finish and then to victory, winning 40.88 percent of the vote. Bill Thompson was second at 26.14%, Quinn in a distant third at 15.74%, and city Comptroller John Liu at 6.84%. Anthony Weiner, who would definitely never run for office ever again, won 4.94%.

Now allow me to engage in some electoral sociology and results analysis to just show exactly how remarkable de Blasio’s victory was. First off, de Blasio won every borough in the city. But even that doesn’t truly demonstrate the scale of his victory and the size of his coalition.

Naturally, de Blasio ran up the score in brownstone Brooklyn. A progressive reformer winning big majorities in Park Slope and Boerum Hill is hardly surprising though. What’s more interesting is how de Blasio routinely won majorities in overwhelmingly minority precincts in Brownsville and East New York. In terms of majority-Black and Latino Brooklyn, you could walk from Sunset Park through Prospect Lefferts Gardens to Spring Creek Towers without ever leaving a de Blasio precinct!

(Let me know if you actually want me to do “the de Blasio 2013 walk”)

Even in areas where de Blasio did comparably worse, such as south Brooklyn, which has a large Modern Orthodox and Conservative Jewish vote, he performed quite impressively. Midwood for example, home to the the conservative weekly The Jewish Press which enthusiastically endorsed Bloomberg in 2009, routinely gave de Blasio enough votes to win a solid second place behind Thompson. Take Election District 48-056, home to the East Midwood Jewish Center (where fun fact, I have played basketball, and no they don’t have a three-point line on their court). This precinct is overwhelmingly Conservative and Orthodox Jewish and elderly, but de Blasio got 25.8% there, good enough to be way ahead of Quinn. Bloomberg had dominated these areas in 2009 to the tune of over 80% but Quinn’s embrace of the outgoing Mayor couldn’t even get her in third place. It’s quite likely Quinn suffered with more conservative religious voters (here and elsewhere) due to her sexuality, but that’s still a shockingly low number. This result is important because even in areas that historically favored Bloomberg, de Blasio still found a constituency. That is how big he won.

The de Blasio landslide extends well beyond Brooklyn. He dominated the northern coast of Staten Island, beat out Thompson in Harlem, defeated Quinn in the LGBT-heavy West Village, won over Black homeowners in Springfield Gardens, won Dominican-American voters in Central Harlem, triumphed in diverse Jackson Heights, and crushed it in Long Island City. Please, check it our yourself. It’s fascinating.

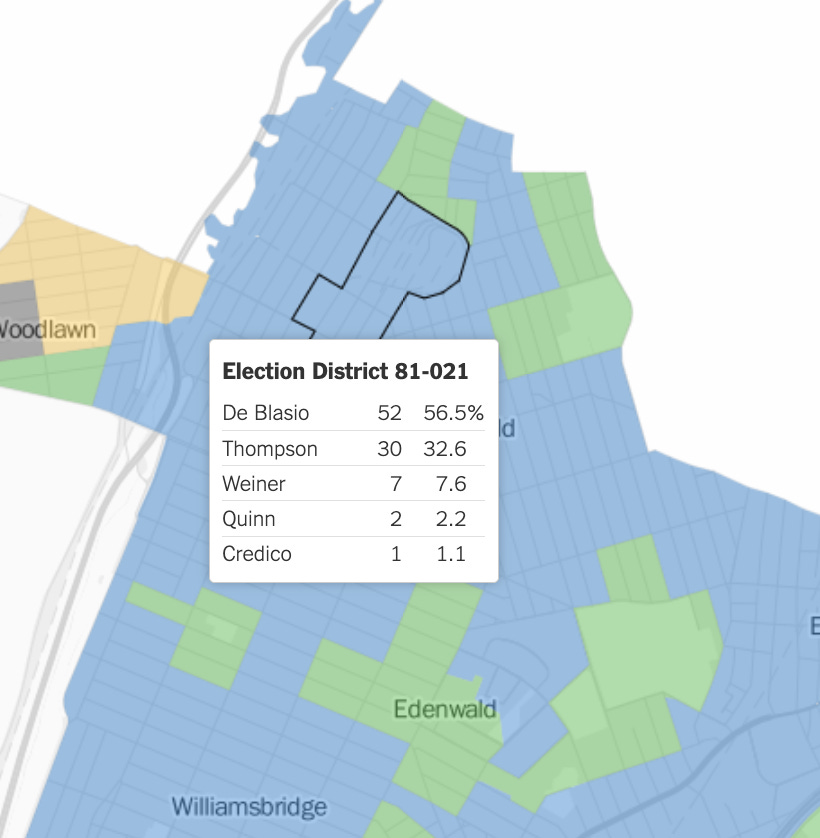

We discussed in Part I, and in this part, specifically which parts of the city were most hostile to Bloomberg in 2009. One such area where Bill Thompson performed very well against Mayor Bloomberg was Wakefield in the north Bronx. Wakefield is overwhelmingly composed of Guyanese and Jamaican immigrants, working-class, and suffers from poor access to the public services. It is in some ways a microcosm of the cracks in Bloomberg’s shining city. If we look to Election District 81-021 in the heart of Wakefield, where Thompson received 67% in 2009, de Blasio received 56.5% despite being virtually unknown there prior to the election. Christine Quinn, the candidate of continuity, won 2 votes. That’s right, 2 votes.

It’s telling that Quinn’s best numbers were in the heart of Bloombergland, the luxury apartments alongside Central Park and in the Upper East Side. In Election District 73-071, home to the beautiful and world-famous Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bloomberg received over 90% in 2009, Quinn won 47.6% in this primary, and de Blasio was in third at 23 percent. Bloomberg’s biggest beneficiaries backed his chosen successor, but it doesn’t seem that the credibility he offered her extended much beyond his core supporters.

The voters had spoken. Bill de Blasio was to be the Democratic nominee for Mayor of New York City.

The Democratic establishment of New York City, cowed by the Bloomberg landslide in 2005 and his towering approval ratings, had conceded the political playing field to him in 2009. They did not count for the resentment that would engender. It should have been clear after Bloomberg barely beat Thompson in 2009 that Democratic voters were not all-in on Bloomberg. Despite that signal, Quinn and the Democratic establishment acted as if they were and largely acquiesced to Bloomberg’s vision of economic recovery and public safety which placed the burden on the city’s poor. In doing so, they neglected their own voters, especially the Black voters which were historically the most loyal to the party. De Blasio took a risk, a risk to defy the powerful Mayor and his established networks, and he spoke to these concerns in a way other candidates were not. His chance paid off and as a result he became the vessel for a citywide, cross-race, cross-borough rebellion against the establishment. This was the de Blasio Revolution.

Would you like to see the Revolution continue into a Part III? Let me know in the comments below.

Part threee part threeeee