The de Blasio Revolution (Part I)

Forgotten today, but Bill de Blasio once led a political movement which would change New York City forever. This is that story.

Let’s turn back the clock.

It is sometime in early 2008. Michael Bloomberg, multibillionaire Mayor of New York City and founder of Bloomberg L.P., is in his Upper East Side mansion, or perhaps at a luxury vacation destination somewhere in the Caribbean (or perhaps American Samoa, I hear he’s popular there). The Mayor has been seriously considering an independent presidential campaign for some time, hoping for extremist nominees in both parties to create an opening for his message of centrist managerialism. Now, he’s looking through a pile of papers with numbers from his pollster. The message is clear, the public has no serious interest in his candidacy. Perhaps the Mayor complains about the vice grip of two-party politics. More likely, the Mayor grimaces in frustration at the folly of the American public. Whatever his reaction, the Mayor is no fool. He wasn’t interested in running to “shift the debate” or such nonsense. He wanted to win. If he can’t win, he won’t run. Very well, he resolves, I will have a third term as Mayor. The law says it’s illegal? I’m the Mayor, I will make it legal.

That is where it began.

On the other side of this drama sits New York City Council speaker Christine Quinn. Quinn is herself interested in the Mayor’s office. The new City Council speaker is already a trailblazer, being the first woman and openly gay speaker, and is just starting to build a citywide brand beyond her West Village district. When Bloomberg tells her he intends to rewrite the law limiting city officials to 8 years in office, she’s hesitant. She had just rigidly committed herself to the two-term limit in 2007 when the issue was first raised, not to mention she was hoping to run in 2009 herself. But the Mayor and his team of well-connected operatives is adamant.

If Quinn crosses the Mayor, she risks the possibility of her own political destruction. The Council had been roiled by a misuse of funds scandal, and if Quinn pressed ahead with her plans then Bloomberg could be well positioned to make sure even if Bloomberg could not serve three terms, then Quinn would serve zero. So ultimately, Quinn resolves that if she’s to be Mayor, she’ll be the candidate for continuity with Michael Bloomberg in 2013. After all, Bloomberg is very popular, what could go wrong? So, Quinn utilizes her legislative skill and establishment authority to whip her Democratic caucus to approve revising the law to allow the Republican-backed Mayor to seek a third term. The measure passes 29-22, a serious credit to Quinn’s skill.

City Councillor Bill de Blasio votes no.

For Mayor Bloomberg, actually winning a third term is an afterthought. He has unlimited financial resources, the support of prominent Democratic politicians, and the sure endorsement of the New York Times. Although polls in 2009 give Bloomberg a 16-point lead over probable Democratic nominee Bill Thompson, the truth is that all is not well in Bloomberg’s New York City. There’s tension under the glamorous surface of his unideological technocracy.

The first of these tensions is class tension. Since Bloomberg became Mayor in 2002, wealth inequality has exploded. In 2002 the wealthiest 1% of New Yorkers held about 25% of the adjusted gross income, and by 2007 that number has grown to 45%. While inequality had certainly increased across the country, New York City stood out as the most extreme example. What’s more, despite substantial economic growth, wages remained stagnant. It’s a striking dynamic of inequality and economic desperation which Bloomberg hasn’t had a solution for.

The second of these tensions is racial. In 2009, the New York Police Department set a record for controversial “stop and frisks” whereby officers temporarily stop, interrogate, and search people on the street deemed a potential threat to public safety. Over 400,000 New Yorkers were treated in such a manner, 90% of whom had no weapons or contraband, and who were disproportionately Black and Latino New Yorkers. This was far from the only problem facing Black and Latino New Yorkers, considering these people were also the most likely to be poor, with less access to affordable housing, electricity, and quality food. Mayor Bloomberg seemed poorly positioned to reckon with this, after all this is the same guy who said that the 2008 financial crisis could be partially blamed on the end of racially discriminatory redlining policies.

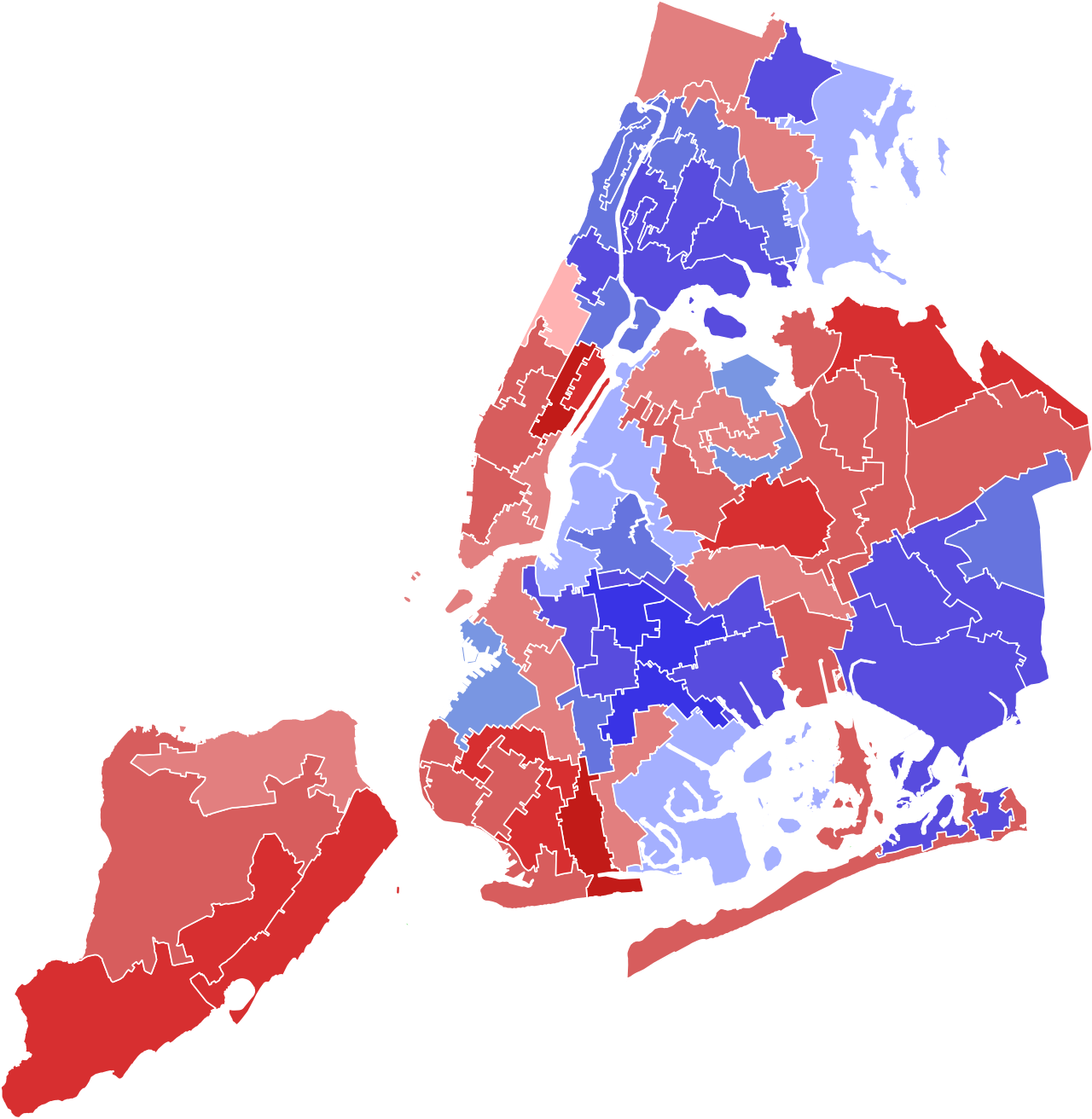

Perhaps that is why, although late polls projected a double-digit victory for the Mayor, the actual voters only re-elected Bloomberg by a less-than-impressive margin of 50.7% to 46.3%. City Comptroller Bill Thompson, who is Black, performed best in the predominantly Black, cash-poor neighborhoods of the south Bronx, east Brooklyn and east Queens. Bloomberg’s best neighborhoods were in the predominantly white, extremely wealthy, Upper East Side. The tensions in Bloomberg’s New York were on full display. Nevertheless, a win is a win, and Bloomberg had secured the third term he so coveted.

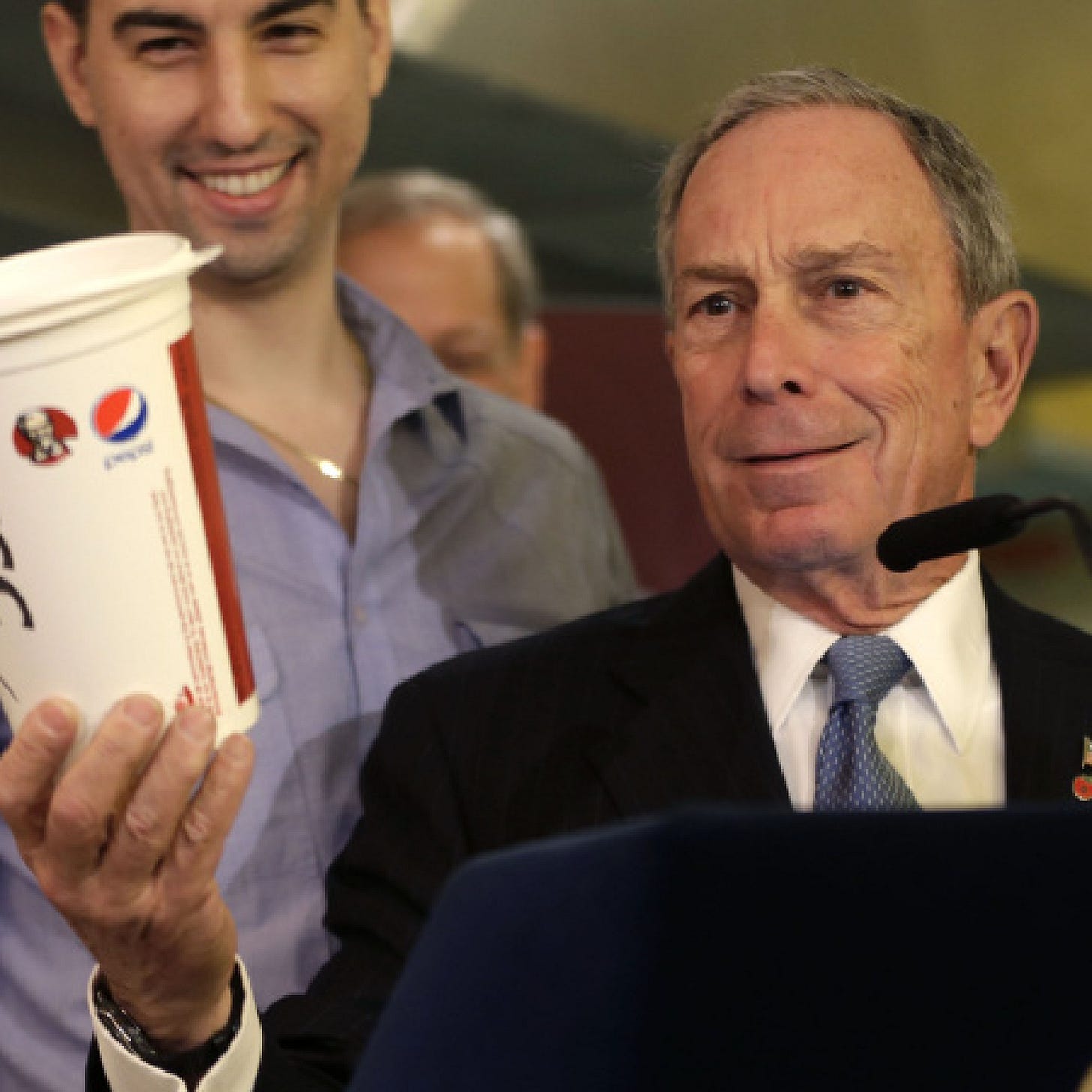

Bloomberg’s third term was marked by the acceleration of racial and economic tensions in the city. It seemed winning a third term had convinced the Mayor that he really could govern New York City exactly like he ran his companies. Perhaps that is why he appointed Cathie Black, a former magazine executive with absolutely no experience in education, to be Chancellor of the largest school system in the country. It was an appointment that lasted three months. At the same time, Bloomberg massively ramped up stop-and-frisk, setting new records for stops and triggering significant public protest. His budgets also placed the burden of economic recovery on the city’s most vulnerable, including proposing cutting 16,000 daycare slots, cutting almost 7,000 teachers, raising caseloads for child services workers, and even cutting the amount fire companies. All necessary to avoid raising taxes of course. That’s all without mentioning his bizarre (but perhaps overly vilified) crusade against large soft drink sizes. The city was beginning to tire of Bloomberg and his austere ways, and his approvals reflected as much.

As the 2013 mayoral election approached, City Council speaker Christine Quinn is finally able to make her move. Stylistically, she couldn’t be more different then Bloomberg. Whereas Bloomberg was an introverted manager who preferred the safe confines of his office to the campaign circuit, Quinn was a gregarious campaigner who relished hugging strangers and traveling across the city. Substantively however, Quinn was the candidate for Bloomberg continuity. Not only did they share staffers and consultants, but as early as 2012 Bloomberg had made it clear she was his preferred successor. Quinn had every reason to be optimistic that her time had finally arrived. She was the anointed one. Not only did she possess the support of the Mayor’s office, but also the Democratic Party machine, including many prominent elected Democrats, Queens County Democratic boss Joe Crowley, and the leadership of the city’s best-connected labor unions. If that wasn’t enough, a Quinnipiac University poll in January, 2013, had her at 35 percent, 24 points ahead of her nearest rival.

Her nearest rival? Public Advocate Bill de Blasio.

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about Christine Quinn and Michael Bloomberg, but very little time about our protagonist. This is the de Blasio Revolution, is it not?

Bill de Blasio was born Warren Wilhelm Jr. in Manhattan on May 8th, 1961. His father was of northern European background, but it was his mother he was close to, and renamed himself accordingly, taking her Italian family name. De Blasio quickly excelled in New York City politics, eventually ingratiating himself with the Clintons and becoming campaign manager for Hillary Clinton’s successful campaign for U.S. Senate in New York in 2000. In 2001, he ran for office for the first time, successfully getting elected to the New York City Council from the 39th district. In the City Council he developed a reputation for having concern for the city’s poor, and in 2009 successfully got himself elected as the city’s Public Advocate (a sort of public Ombudsman or watchdog).

As Public Advocate, de Blasio became Mayor Bloomberg’s strongest critic. He led public fights against Bloomberg’s proposed budget cuts, criticized his pick for schools Chancellor, and had successes in forcing the all-powerful Mayor to change course. An instructive contrast was developing. Christine Quinn was the candidate of the insider track of city politics, of the status quo, and de Blasio was the candidate of change. On paper, Quinn should have had no problem obtaining the Mayor’s office. She had the big endorsements, she had the Mayor and his extremely well-connected network, and she could rely upon a coalition of affluent Manhattanites and outer borough machines to deliver her to a primary victory.

This was on paper. But out on the streets, the 12 years of Bloomberg had taken a toll. People resented the way he got his third term, they resented the way Democrats shoved aside Bill Thompson to do it, and people resented the establishment. Something special was about to happen.

To be continued in Part II…